GI Joe or Transformers? Sega or Nintendo? Hero or Hercules? Pretty much anything I remember from my childhood – be it action figures, video games or cycles, etc. – I always had only very few brands to choose from. As a result, my choices were pretty simple: Pick whatever most of my friends had, and it always worked out for the best.

But today, children are spoilt for choice. Every movie or cartoon comes with its own set of merchandise, with tiers and variants within each. From The Avengers and X-Men to Dragon Ball Z, One Piece to Pokémon and more, there is so much to choose from. If you take gaming for example, it’s the same. Consoles like PlayStation, Xbox and Nintendo or PC? And even within PC gaming, do they choose Steam, Epic, Origin or Uplay? Or should they just choose mobile gaming? When I bought my first cycle, I considered myself lucky because the only bike that was the right size for me in the store just happened to be a cool-looking black and red colour bike. Now, kids can choose between a street, race or mountain bike from Firefox or Schwinn or Giant or B’Twin.

The problem of choice is all-pervasive today. It isn’t just kids’ toys and games and cycles. Look around, there are more brands everywhere, and they are available in more places, advertising to you in more ways than ever before.

Back when I bought my Hero Devil (the aforementioned cool-looking black and red bike), there was no internet. I had originally set my mind on a Hercules Cannon Barrel because of an ad I saw in the newspaper. Sadly, they didn’t have it in the store and I ended up with what was available, which was cool too.

Advertising in those days was primarily through print (newspapers & magazines), TV, radio and hoardings. There were only so many big brands with the budget to do mass-media advertising. So communication was completely One-to-Many – brands put out an advertisement that was aimed at a large cluster of people amongst whom were the target consumers who they thought were likely to be interested in what they were selling.

As the number of brands increased, with a corresponding increase in those that had access to mass media, targeting and niche marketing came to the fore. But this only took off effectively when the internet, and then mobile phones with 3G came along. Suddenly everyone was online, and advertising wasn’t as expensive anymore because you could now target very specific ads to small, select groups of people at certain times in select places.

Thus the One-to-Many changed into a One-to-Few.

This happened around the time when I got into marketing, making my way in to digital media. The only thing I really knew was that most brands didn’t know much about anything in new-media because the digital landscape was so dynamic, evolving very quickly. Eventually, as technology, tools and practices became more attuned to this evolving nature of media; platforms like Google and Facebook became more popular – not just as customer platforms but more so as powerful marketing engines – the One-to-Few evolved and became the One-to-One where specific brands could target very specific customers.

But what was truly interesting was that customers could now talk back, because these platforms had given them a voice and a reach they never had before.

Customers had gained the power to respond to brand communication in very visible ways – through social media, e-commerce and a range of other platforms built by brands to aggregate their customers. Brands could be commended for a great product or service and condemned if they failed to deliver on their promise or delivered a sub-par experience.

In the last couple of years however, we have seen a flip, a power shift in the direction of this One-to-One relationship, where customers are raising their voices by reviewing, sharing their experiences and more often than not, publicly complaining about brands.

Reddit, Zomato and Metacritic have built an entire business on this voicing of customer opinion. Companies like Amazon use it as an effective mechanism to help other customers make informed/influenced decisions.

As people got more comfortable with being heard, a lot of them started to enjoy it and morphed from commenters to publishers. My favourite example is Linus Sebastian who started with a small time YouTube channel for the now defunct Canadian computer store called NCIX. When he started, he was a category manager with no budget and borrowed video equipment. Today, he has the 5th most watched YouTube channel, and over 13 million followers across channels. He also owns an entire media company and makes some of the most educational and enjoyable tech content on YouTube.

Today, such publishers and influencers have massive followings, enabling them to reach tens of millions of people instantly. These influencers work with multiple brands who rely not just on their fame, but also on the channel on which they broadcast to create positive impact for their brand – to the extent that many of them have more clout than the companies that contract them!

Companies now need influencers to work with them (not for them) in order to gain traction with the right set of customers.

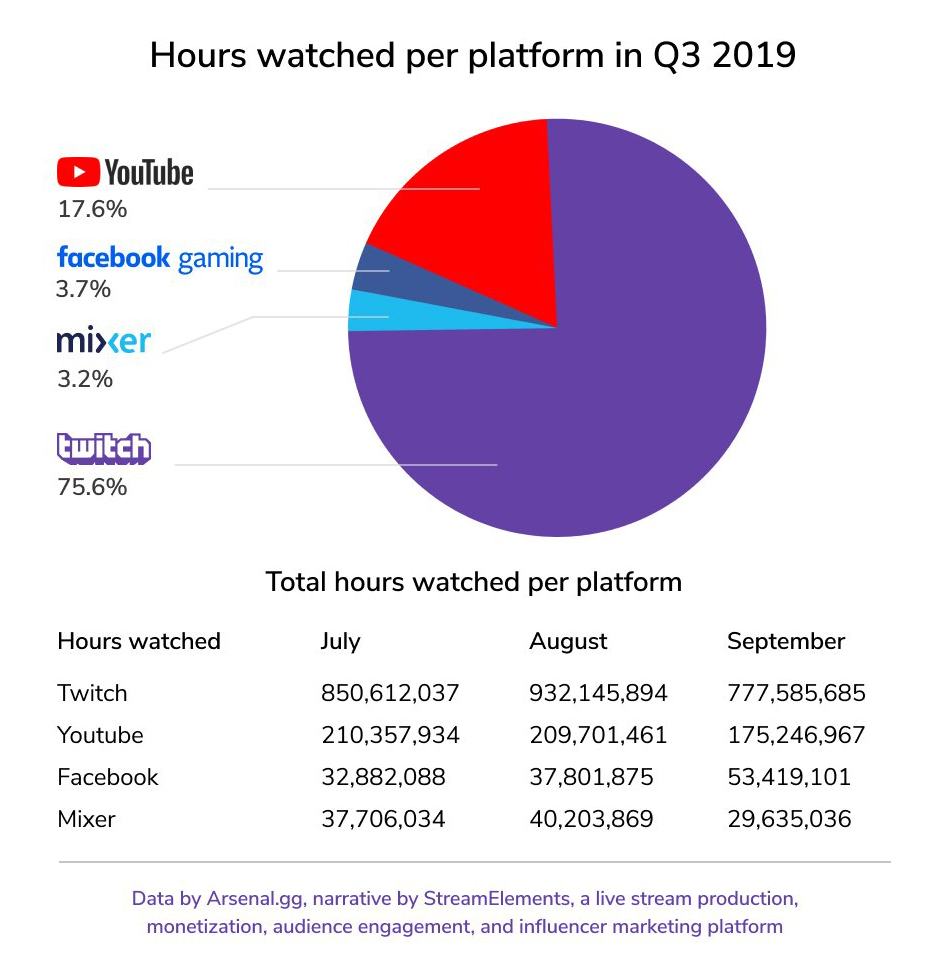

To cite an example, a couple of months ago, to take away viewership from Amazon’s Twitch, Microsoft-owned Mixer bought out Twitch’s biggest star, Tyler ‘Ninja’ Blevins, for $50 Million to play Fortnite while fans watch. After a shift to Microsoft, and a quick tweet later, Blevins had almost a million followers on Mixer in next to no time.

The above would be a case of Few-to-One where a few large influencers hold sway over a brand. If one large influencer with enough clout decides to give your phone or movie a negative review, it can severely affect sales and profitability to say the least. Just today, I learned that Days Gone, (don’t worry if you don’t know it) a game I quite enjoyed, won the Game of the Year at the Golden Joystick Awards. However, because the game was given a ridiculously low score by big game reviewers at IGN and Gamespot, it sold poorly and I was able to get it on sale for very cheap very early on. But well, that’s the power of clout for you.

Another prominent scenario nowadays is where a lot of people online can drastically change something they don’t like, just because they have collectively decided to. I call this the case of Many-to-One.

A recent example of this are the fates of David Benioff and D.B. Weiss, the writers of Game of Thrones, whose last season saw overwhelming negative criticism for ruining a fan favourite series with poor writing. The backlash was so strong that Disney dropped them both from a future Star Wars trilogy project they had been signed up for. The movement was led by r/freefolk community on Reddit who were audaciously loud about their discontent with how the writers finished off the series.

Another example of Many-to-One in action is that of the upcoming Sonic the Hedgehog movie. Sonic was the mascot for Sega (I played as the Blue Blur, not the Plumber by the way) and a character that many of us early gamers grew up adoring. When the first movie trailer came out, it was alarming (and not in a good way) how realistic Sonic looked. He wasn’t his cool slick speedy self. He looked quite literally like a blue furry hedgehog and that didn’t sit well with fans. After a fair amount of outcry on pretty much every social platform by fans worldwide, by the time the second trailer hit, the design team had gone back to work and fixed Sonic to be what the fans wanted to see.

This change reportedly cost the producers upwards of $5 million. But that’s the cost of doing business in a world where the customer has a voice, and is louder than you, and with enough momentum can sink an investment, franchise or even a nation. It is quite the utopian notion of democracy manifest.

Things always come full circle, and so it has in marketing and communication. It has gone from the One-to-Many of old, where it was the brands that were dictating terms, all the way around to Many-to-One where the consumer has all the power.

On the brand side, enabled by AI, IoT, sensor technology and enhanced tracking metrics, this behaviour and pattern will only get amplified in the coming days and lead to a new Many-to-One scenario where a large number of brands will compete for the attention of each individual consumer. Welcome to the attention economy, where we will each receive truly personalised and completely customised advertising communication with a target of 1, precisely at the right time and in exactly the right place, all to maximise the probability of conversion.

Which begs the question, if the consumer is so sought after, at that level of interest, who is the more valuable brand – the customer or the company?