Of course EVs are good for the environment, but that’s not the real reason why they are beginning to disrupt mobility solutions. The real power of EVs is in the economic impact. However, the impact needs to be large enough to disrupt our dependence on internal combustion engined vehicles.

The IC-engine came into our lives in 1876, when Nikolaus Otto, working with Daimler and Maybach, patented the compressed charge, four-stroke cycle engine. Then on July 3rd, 1886, Karl Benz in Mannheim, Germany, drove the automobile into our lives. Though many alternatives were tried, such as the two-stroke in late 1800s and the Wankel engine almost a century later, nothing could beat the reliability and performance of the 4-stroke engine.

Our lives have revolved around the certainty of mobility based on the compressed charge four-stroke engine.

As with all technologies, billions of dollars have been spent squeezing more power, performance and economy out of converting chemical energy to mechanical energy. However, the laws of thermodynamics are inviolable and very little can be squeezed out of the IC engine any more. Then there is the issue of emissions, particulate and gaseous, threatening our lives and the planet. This consciousness is now manifest in regulatory strictures. It is also driving up costs as cars have to now comply with emission norms. The product life cycle of the IC engines has entered the decline phase and electric vehicles is the next big opportunity.

Electric vehicles are not new. They came into being around the same time as internal combustion engined cars. They were in fact better – noiseless, easy to drive without any need for gear change and no smelly exhausts. But electricity wasn’t readily available and batteries were primitive giving cars very limited range. Cheap, universal availability of petrol and later diesel in the early 20th century and the economics of mass production made IC-engined cars affordable, available and convenient.

Global economy has been, for more than a hundred years, powered by the IC engine. But that’s about to change rapidly.

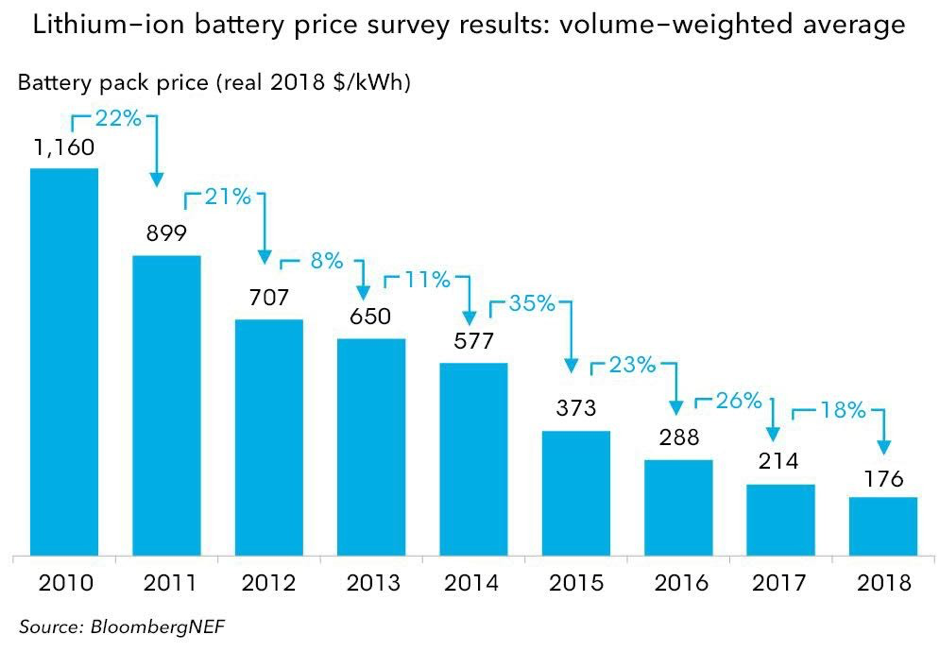

The arrival of Lithium ion cells and the continuous improvement in battery chemistry development allows more electrical charge to be packed in smaller and lighter batteries. Couple that with the fact that battery prices have sharply dropped between 2010 to 2018, from $1160/kwh to $176/kwh.

And now there is even better news. John Goodenough, the inventor of lithium ion batteries has invented a new solid state lithium battery which boasts triple the energy density of standard Li-on batteries, along with a much higher longevity.

The current TCO (Total Cost of Operation) has already positively impacted fleet operators like Lithium Urban. Currently battery price constitutes between 20-30% of the cost of an EV depending on the type of vehicle. New batteries based on Lithium Metal and solid state should get commercialised in the next 3-5 years and its superior economics and higher charge density will swing the market to rapid growth phase.

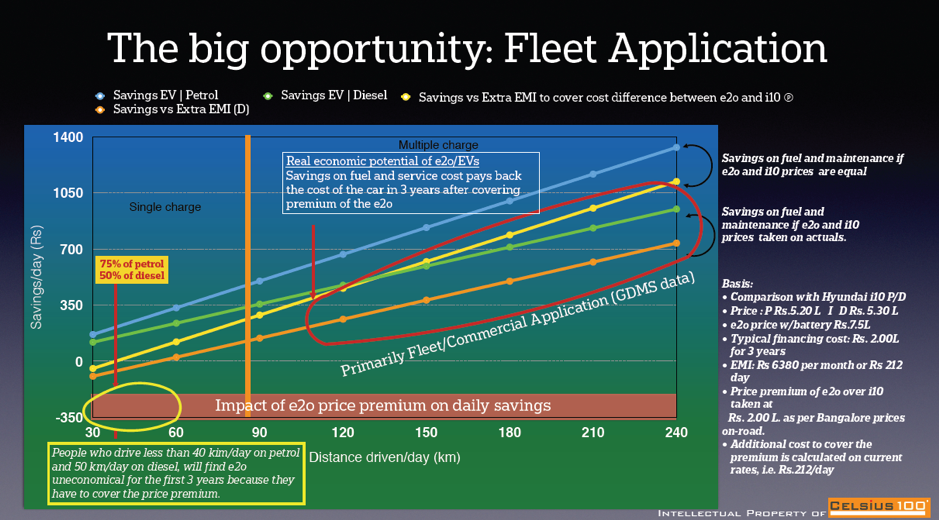

5 years ago, when battery prices were around $570/kwh, I did a cost comparison test between the E2O and the Hyundai i10, petrol and diesel driven over hundreds of kilometres, for Reva Electric, I also went through the Global Dealer Management System databases in India to determine the average daily distances driven for individual and commercial applications. The computation of the cost economics also took into account the additional EMI to be paid for the higher cost of the E2O. The data was quite revealing. It made no sense at that time to go electric for those driving below 40-50 km/day. The blue and green curves are savings against petrol and diesel. The yellow and brown lines are savings with the E2O cost premium impact. With battery prices now less than 30% of those prices, the economics has significantly shifted in favour of electrics.

I also conducted extensive attitude and behaviour research and arrived at the following conclusions:

- We prefer uninterrupted journeys. Whether we fly, take the train or the road, non-stop is always a better proposition. The IC-engined automobile conforms to this ‘non-stop’ mobility need, thanks to the universal availability of petrol or diesel and a few minutes to tank up.

- The perception that electric vehicles takes hours to charge signals interrupted journeys, completely unacceptable to all consumers. Lack of charging infrastructure exacerbates the perceptual block.

- The issue of recurring capital cost of battery is a serious financial barrier and cannot be mitigated unless a leasing model is in place.

- The lack of certainty of resale value of EVs lowers the value of the asset and makes it an unattractive value proposition.

- Almost complete lack of knowledge and familiarity with EVs is possibly the biggest barrier.

- The absence of significant product choice and communication in this segment is severely affecting the attractiveness and credibility of EVs.

In essence there are layers of fear associated with electric vehicles amongst most individual buyers.

The consumers who are buying, though minuscule in number, are habitual explorers of new technology or drive very short distances and attracted by the promise of wearing the green badge, a talking point in their peer group with the alibi of very low operating costs.

There is however a natural ally for EVs now: Fleet Operators, for whom EVs are a boon, due to many reasons, including:

- The amplification of the disruptive economic impact of at least 5x savings per kilometre makes significantly more sense to a fleet operator with 5-8x higher asset utilisation as it results in massive savings for the fleet operator and user.

- Operating a predictable journey cycle allows charge scheduling and instils confidence

- The fact that there are no consumables needed and no usual maintenance costs (due to lack of moving parts like engine, gearbox components, clutch assembly, cooling, lubrication and exhaust system etc.) translates into significant savings for a fleet operator.

Sanjay Krishnan and Ashwin Mahesh were seized of these advantages when they founded Lithium Urban Technologies.

They focused on predictive journey opportunities, invested in fast and normal charging infrastructure and custom built a software-based ecosystem to ensure the real-time monitoring of vehicles, charge scheduling and deployment. Lithium has brilliantly leveraged the many advantages that EVs deliver in fleet operation to become the largest EV fleet operator in the world outside China and win global awards for sustainable urban mobility.

The advantages and economic benefits are just too big to ignore for any serious fleet operator who operates in the urban mobility space. The disruption has begun, the end of the IC engine is in sight.